The invention of paper money was one of the most transformative developments in global finance, and its origins are deeply rooted in Chinese history. China's pioneering role in developing paper currency and its relationship to Europe's later adoption of similar systems offers crucial insights into how modern financial systems evolved. The introduction of paper currency in China revolutionized the concept of money and laid the groundwork for economic concepts that underpin modern financial systems. These advancements influenced monetary theory and practice worldwide, particularly the concept of “layered money”—the idea that money can exist in different forms and levels of trustworthiness, each layered on top of the other in a structured hierarchy.

The invention of paper money in China wasn't a sudden innovation but a gradual evolution driven by practical necessity. Before the advent of paper currency, China used various forms of commodity money, including shells, precious metals, and even tools like spades and knives. These physical forms of currency functioned as symbols of wealth and provided a basis for trade. The limitations of using commodities for trade—such as weight, portability, and security—eventually drove the Chinese to search for a more convenient alternative. With the advent of coinage in the Zhou Dynasty around the 4th century BCE, metallic currency became prevalent in China, mainly copper coins.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), the increased volume of trade during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) and the expanding needs of a growing population created challenges. Merchants faced a significant challenge: copper coins were heavy, and long-distance trade required transporting large quantities of metal currency. The solution emerged from a practice that began in Sichuan province, where merchants would deposit their heavy coins with trustworthy shops and receive a paper receipt - known as "flying money" (feiqian) - in return. These were used mainly by merchants within the government-run salt trade. This system foreshadowed the development of the more sophisticated paper currency issued by the Song Dynasty in the early 11th century.

These early promissory notes marked the first layer in what would become a sophisticated monetary system. The paper receipts weren't technically money but claims on the underlying metal currency. This distinction is crucial for understanding the concept of layered money: the base layer (copper coins) served as the foundation for a more convenient second layer (paper receipts).

The transition from private receipts to government-issued currency occurred during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE). The Song government began issuing official paper money around 1024, a move that was initially intended to address a shortage of copper coins. Known as "jiaozi," this early currency was backed by the state and widely accepted within the empire. The convenience and practicality of jiaozi led to its rapid adoption among both merchants and the general population.

What's particularly remarkable about China's monetary system was its sophistication. The Song Dynasty understood concepts that wouldn't be fully grasped in Europe for centuries. They recognized that:

1. Currency value needed to be managed through a controlled supply

2. Different regions might require different monetary policies

3. The relationship between metal reserves and paper money needed careful balance

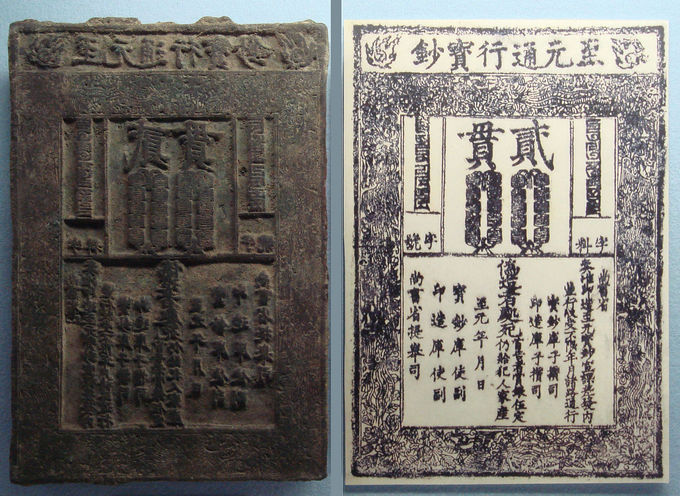

The Song government established exchange bureaus where people could convert paper money to coins and vice versa. They also implemented anti-counterfeiting measures, including detailed artwork and special paper with fiber patterns. These innovations demonstrate an understanding of the practical and theoretical aspects of managing a paper currency system.

The concept of layered money can be applied to these early forms of paper currency in China. Layered money, as described in modern monetary theory, posits that there are different levels or "layers" in the structure of money, each with varying degrees of creditworthiness and liquidity. The hierarchy starts with base money (often physical assets like gold or central bank reserves). It extends to higher layers, such as paper notes and credit instruments, which depend on trust in the issuer.

In ancient China, the foundation or base layer of money was initially copper coinage, which held intrinsic value and could be directly exchanged. Paper currency, which evolved as a second layer, relied on trust in the state’s promise of convertibility into coinage or other physical assets. This system required the public to believe in the government’s capacity to uphold its obligations, which in turn linked the paper money to the reliability and creditworthiness of the issuing authority. Each layer builds upon the trust and stability of the layers below it. Each layer represents a different level of abstraction from physical commodity money, requiring increasingly sophisticated systems of trust and verification. This hierarchy of money forms wasn't just a Chinese phenomenon - it's a pattern that repeats throughout monetary history and shapes our understanding of modern financial systems.

During the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), the Mongol rulers of China expanded the use of paper currency even further. Under Kublai Khan, a system known as "chao" was implemented as the official currency of the empire. Marco Polo, who traveled to China in the late 13th century, documented this unique monetary system in his writings, describing it as an elaborate and organized state-backed currency system. He marveled at the Chinese willingness to accept paper currency in exchange for goods and services, noting that it was a practice unlike anything in Europe at the time.

However, this early experiment with state-issued paper currency also highlighted the risks associated with inflation. The Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) showed how paper money could be mismanaged. As the government increased the amount in circulation to fund wars and administrative costs, the currency’s value began to decline. Their excessive printing led to severe inflation, providing an early historical example of the risks inherent in fiat currency systems. Although the Yuan Dynasty’s experiment with paper currency ultimately failed, it provided a crucial case study of the complexities of layered money and the necessity of maintaining confidence in higher layers of monetary value.

When we turn to Early Modern Europe (roughly 1500-1800), we see a markedly different approach to paper money and financial innovation. In contrast to China, early modern Europe was slow to adopt paper money. European economies were grounded in metal-based currencies—primarily silver and gold coins—that were widely trusted for their intrinsic value. The culture of using coins made Europeans wary of paper money, which was seen as a novel and potentially unreliable alternative. It was not until the 17th century that European countries began experimenting with paper currency, driven by the emergence of central banking institutions and the growth of state-backed financial instruments.

European paper money emerged primarily through private banking institutions rather than direct state issuance. The Bank of Amsterdam, founded in 1609, and later the Bank of England (1694), played crucial roles in developing Europe's paper money systems. These banks issued promissory notes, which could be redeemed for gold on demand. These notes effectively served as a second layer of money, backed by a reserve of precious metals—similar to the layered system that had emerged centuries earlier in China. Unlike in China, however, the transition to paper currency in Europe was gradual, influenced by the complex interplay of state power, economic necessity, and public skepticism.

The European approach reflected a different social and political context. In China, paper currency evolved organically within a largely centralized system where the state played a direct role in issuing and regulating money. This direct involvement allowed for rapid adoption but also made the currency vulnerable to mismanagement and inflation. In Europe, by contrast, the emergence of layered money was tied to the rise of private banking and the creation of institutions like the Bank of England, which operated under a framework that included accountability measures and legal structures.

The European model benefited from its reliance on state and private actors, creating a system in which trust in the currency was more decentralized. Furthermore, by anchoring paper currency to gold or silver reserves, European banks could maintain greater public confidence in their notes, mitigating the risk of inflation that had plagued the Chinese paper money system. The economic context also shaped these divergent paths significantly - China's vast unified market naturally encouraged the development of standardized currency across its territories. In contrast, Europe’s politically fragmented landscape led to competing monetary systems. These distinctions also manifested in their innovation patterns. While China pioneered early paper money technologies and their practical implementation, Europe ultimately developed more sophisticated banking and credit systems through its competitive banking landscape.

The historical experiences of both China and Europe with paper money offer valuable insights for understanding modern monetary systems. Trust proved essential to monetary function, whether that confidence was backed by imperial authority or banking institutions. Both regions also learned through experience the importance of balancing money supply with economic needs. Their experiences demonstrated that monetary systems evolve iteratively through trial and error, building on previous successes and failures rather than emerging fully formed. Both cases showed how successful monetary systems must reflect their broader social, political, and economic environments to function effectively. These historical lessons remain deeply relevant today as we continue to see innovation in monetary forms, from digital currencies to cryptocurrency. The concept of layered money helps us understand how these new forms can build upon existing systems while adding new levels of abstraction and utility, just as paper currencies once built upon and abstracted from metallic money.

The history of paper money in China and Europe demonstrates how different societies can develop similar financial innovations through different paths. China's early experience with paper currency provided valuable lessons about monetary management, while Europe's later development of banking institutions added new dimensions to financial innovation.

Understanding this history through the lens of layered money helps us appreciate the complexity of monetary evolution. Each new layer of financial innovation builds upon previous developments, creating increasingly sophisticated systems for storing and transferring value. As we continue to see new forms of money emerge, these historical experiences remind us that successful monetary innovation requires balancing technological capability with social trust and economic necessity.

The parallels between historical monetary innovations and current financial developments suggest that while the specific forms of money may change, the fundamental principles of monetary systems remain consistent. Trust, proper management, and adaptation to local conditions are essential to successful monetary systems, whether dealing with the Tang Dynasty flying money or modern digital currencies.

Listen to Episode 57

Dumas said, 'If you come to link this market to bring what the others have been doing for generations, there's no point,' Dordet recounts. "He told them, 'Please be as different as possible in terms of style, link fantasy, link or humor. Maybe people will like it, maybe they won't, but at least we will have tried something new.'"