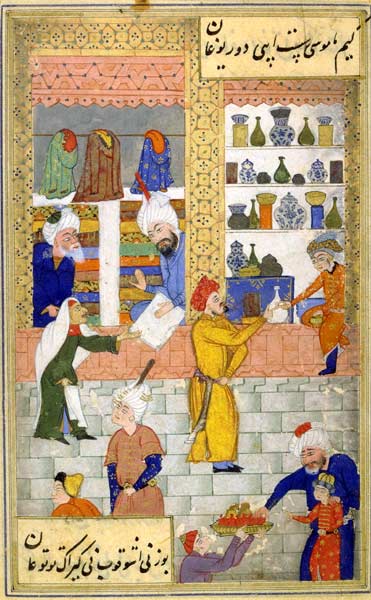

Left: Coffe and porcelain merchants. Haydar Khwarizmi, 1550

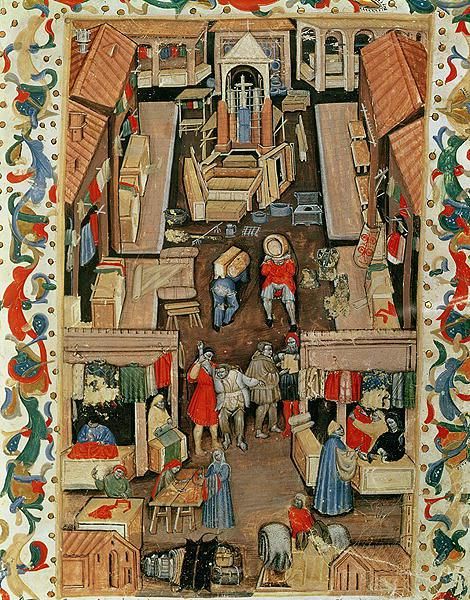

Right: The Porta Ravegnana market in Bologna – Miniature from the Freshmen of the Drappier Society, 1411

Guilds played a pivotal role in shaping the economic, social, and cultural landscapes of the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe from the Middle Ages through the early modern period. While sharing fundamental similarities in their basic structure and economic functions, Ottoman and European guilds also exhibited significant differences, reflecting their distinct cultural, religious, and political contexts. This essay will compare and contrast guild development, structure, and multifaceted roles in these two regions, exploring how these institutions mirrored and diverged from each other in response to their unique historical circumstances.

The emergence and evolution of guilds in the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe followed different timelines and trajectories. In Western Europe, guilds began to take shape in the 11th to 13th centuries as associations of craftsmen and merchants in growing urban centers. These early European guilds arose primarily as grassroots organizations, forming to protect the economic interests of their members and regulate their trades. They gradually gained official recognition and privileges from municipal authorities and rulers.

Conversely, Ottoman guilds, emerging prominently in the 15th and 16th centuries, were more directly influenced by pre-existing Islamic guild traditions and were closely integrated with the state apparatus from their inception. The Ottoman government, in contrast to its European counterparts, played a more active role in organizing and overseeing guild activities as part of its broader system of economic and social regulation.

Ottoman and European guilds shared a basic hierarchical structure consisting of masters, journeymen, and apprentices. However, there were notable differences in the specifics of this hierarchy and the paths of advancement within it. European guilds typically maintained a rigid hierarchy with clear distinctions between the three ranks. Becoming a master often required completing an apprenticeship, working as a journeyman, creating a "masterpiece" to demonstrate one's skills, and paying substantial fees. This system could be quite restrictive, with mastership often limited to those with family connections or significant financial means.

Ottoman guilds, while also hierarchical, tended to have a somewhat more flexible and inclusive structure. They included additional leadership roles like the yiğitbaşı (head of young workers) and kethüda (guild steward), which provided more opportunities for advancement and responsibility within the guild structure. The path to becoming a master in Ottoman guilds was generally more inclusive, with less emphasis on hereditary privileges and more opportunities for skilled artisans from diverse backgrounds to advance. This sense of equality and opportunity was a defining feature of Ottoman guilds.

In their core economic functions, Ottoman and European guilds shared many similarities. Both systems regulated production, maintained quality standards, controlled prices, and managed market access for their respective trades. Guilds in both regions played a crucial role in training new artisans through apprenticeship systems and preserving and transmitting specialized knowledge and techniques.

However, the degree and nature of state involvement in guild economic activities differed significantly. Ottoman guilds operated under closer state supervision, with government officials often directly involved in setting prices, wages, and production quotas. The Ottoman state viewed guilds as integral parts of its economic management system and used them as instruments to ensure stable supplies of goods and services.

While subject to varying degrees of state regulation, European guilds generally enjoyed more economic autonomy. They often had the power to set internal rules and standards with less direct government interference. This autonomy could sometimes lead to conflicts with municipal or royal authorities over economic policies and privileges.

Guilds' political role and influence differed markedly between the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe. Guilds wielded significant political power in many European cities, particularly in regions like Flanders and northern Italy. They often held seats on city councils, played crucial roles in urban governance, and sometimes even challenged the authority of nobles or monarchs.

Ottoman guilds, by contrast, had less direct political autonomy. They were more integrated into the state bureaucracy and served as intermediaries between the government and urban artisans and merchants. While they could advocate for their members' interests, their political role was more circumscribed and focused on implementing state policies rather than shaping them independently.

One of the most striking differences between Ottoman and European guilds lay in their religious and cultural dimensions. European guilds were closely associated with Christian religious practices. Many had patron saints, maintained altars in local churches, and participated in religious processions and festivals. Their religious activities were generally separate from their economic functions, reflecting European society's gradual separation of religious and secular spheres.

On the other hand, Ottoman guilds were deeply intertwined with Islamic religious traditions, particularly Sufi orders. The religious aspect was not merely an addition to their economic role but an integral part of their identity and function. Guild ceremonies often included religious rituals; many guild leaders held religious titles. This integration reflected the more holistic view of society in the Islamic world, where religious, economic, and social spheres were less sharply delineated.

The concept of futuwwa, or Islamic chivalry, significantly shaped Ottoman guilds' ethical and social norms. Futuwwa emphasized virtues such as generosity, bravery, and loyalty, providing a moral framework that guided guild members' behavior both in their professional and personal lives. This ethical system fostered a sense of solidarity and mutual responsibility among guild members beyond mere economic cooperation.

Both Ottoman and European guilds served important social functions, acting as support networks for their members and contributing to the broader welfare of their communities. However, the nature and extent of these social roles differed between the two systems.

European guilds provided various forms of mutual aid to their members, such as financial assistance during illness or old age and support for widows and orphans of deceased members. They also engaged in charitable activities, often linked to their religious observances. However, their social functions were generally more limited in scope and focused primarily on their members and immediate communities.

Influenced by Islamic principles of social responsibility and the futuwwa tradition, Ottoman guilds often played a broader and more active role in social welfare. They maintained funds for helping members in need, contributed to community projects, and engaged in extensive charitable works. The social support provided by Ottoman guilds extended beyond their immediate membership, reflecting a more communal approach to social welfare.

Moreover, Ottoman guilds often served as important venues for social integration, particularly in the empire's diverse urban centers. They frequently incorporated members from various ethnic and religious backgrounds, fostering a shared professional identity that could transcend other social divisions.

The role of guilds in education and knowledge transmission also exhibited similarities and differences between the Ottoman and European contexts. In both systems, guilds were crucial for vocational training through apprenticeship programs. These programs taught technical skills and inculcated professional ethics and social norms.

However, the content and scope of this education differed. European guild education was primarily focused on vocational training, with broader education generally left to churches and schools. Ottoman guilds, reflecting their more integrated social and religious role, often provided a more comprehensive education that included moral and religious instruction alongside vocational training. For example, an Ottoman apprentice might receive lessons in Quranic recitation and Islamic ethics as part of their guild education. In contrast, a European apprentice typically receives such instruction separately from their guild activities.

The trajectories of guild systems in the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe diverged significantly in the modern era. European guilds began to decline earlier, facing challenges from the rise of industrial capitalism and new economic philosophies emphasizing free markets in the 18th and 19th centuries. Many were officially abolished or lost their privileges during this period, though their influence persisted in some forms.

Ottoman guilds proved more resilient, persisting well into the 19th and early 20th centuries. This longevity can be attributed to several factors, including their closer integration with state structures, their broader social and religious roles, and the slower pace of industrialization in the Ottoman Empire. However, they, too, eventually declined under the pressures of economic modernization and political reforms in the late Ottoman period.

The comparison of Ottoman and European guilds reveals a complex picture of similarities and differences shaped by distinct cultural, religious, and political contexts. While sharing essential economic functions and hierarchical structures, these two guild systems diverged significantly in their relationships with state authorities, religious integration, social roles, and cultural influences.

European guilds, emerging earlier and with greater autonomy, played crucial roles in shaping urban economies and sometimes urban politics. Their religious associations, while necessary, were generally more separate from their economic functions. Ottoman guilds, developing later and more closely tied to state structures, were deeply integrated with Islamic religious and ethical traditions. They played broader social roles and were important instruments of economic regulation and social cohesion in the diverse Ottoman urban landscape.

Understanding these differences and similarities illuminates the specific histories of these institutions and provides insights into the broader social, economic, and cultural differences between the Ottoman and European worlds. The study of guilds offers a window into how societies organize economic activities, structure social relationships, and negotiate the balance between state control and professional autonomy.

As we reflect on these historical guild systems, we can see echoes of their influence in modern professional associations, labor unions, and debates about the role of government in economic regulation. While guilds as formal institutions have primarily disappeared, many of the fundamental issues they grappled with – balancing economic interests, maintaining professional standards, providing social support, and negotiating with state authorities – remain relevant in our contemporary global economy.